The New Mexico Penitentiary Riot: 36 Hours of Hell

February 2-3, 1980 - A Complete Account (Note: This is a long article, you may need to go to Substack to see the entire thing.)

Prologue: The Powder Keg

On a frigid February night in 1980, the wind howled across the high desert surrounding the Penitentiary of New Mexico, located ten miles south of Santa Fe. Inside the concrete walls of the facility built in 1956, tension had been building for months like pressure in a steam boiler with no release valve. What would unfold over the next thirty-six hours would become the most violent prison riot in American history, a savage explosion of brutality that would claim thirty-three lives and forever change how the nation viewed its correctional institutions.

The warning signs had been flashing red for months, but like so many institutional disasters, they were either missed, minimized, or simply ignored by those with the power to act.

Chapter 1: Warnings in the Wind

The Intelligence That Went Unheeded

January 11, 1980 - just three weeks before the riot - Dr. Marc Orner, the prison psychologist, sat at his desk composing what would prove to be a prophetic memorandum. His sources among the inmates had been whispering about something big brewing in Dormitory E-2. The intelligence was specific and chilling: inmates were planning to take hostages, and they had supposedly hidden ammunition and homemade firearms in the dormitory to be used in a takeover.

Orner addressed his memo to Superintendent of Correctional Security Manuel Koroneos, a seventeen-year veteran of the penitentiary who had worked his way up from correctional officer to the prison's top security position. The memo landed on Koroneos's desk with the weight of urgent warning, but when administrators conducted a shakedown inspection of Dormitory E-2, they found nothing. No weapons, no hooch, no ammunition. The warning was filed away, another false alarm in a system plagued by rumors and inmate manipulation.

But the intelligence reports kept coming.

January 23, 1980 - Deputy Warden Robert Montoya received another warning, this time about Cellblock 3, the maximum security unit that housed the prison's most dangerous and troublesome inmates. A confidential informant reported that inmates in Cellblock 3 were planning a hostage seizure after the evening count. Even more disturbing, the informant claimed that inmates in Cellblock 2 were manufacturing knives and distributing them to other inmates for use in the planned takeover.

Montoya, a former Arizona corrections supervisor who had joined the New Mexico system in 1975, took this intelligence seriously enough to recommend that protective custody inmates in Cellblock 3 be transferred out for their safety. A shakedown was conducted - again, no contraband was found. But the pattern was becoming clear to those willing to see it: the inmates were planning something, and Dormitory E-2 remained at the center of the rumors.

The Gathering Storm

Throughout January 1980, the signs of impending trouble multiplied like storm clouds on the horizon. Transfer requests from Dormitory E-2 increased dramatically. Inmates who had never shown interest in leaving their housing assignments suddenly wanted out of E-2. Some cited vague fears; others simply said the dormitory was "getting hot."

The prison's Acting Intelligence Officer, Larry Flood, had only been in the position for two weeks when he observed what he would later describe as an increasingly "ugly" mood among the inmates. Flood, a twenty-three-year Army Military Police veteran who had been working at the penitentiary for two years, possessed an experienced eye for reading institutional tension. What he saw worried him enough to request an emergency intelligence-sharing meeting.

On January 31, 1980 - just two days before the riot - Flood convened what would be the last chance to prevent the coming catastrophe. Present at the meeting were the top echelons of New Mexico's correctional and law enforcement leadership: Deputy Secretary Felix Rodriguez, Warden Jerry Griffin, Deputy Warden Robert Montoya, Central Office Security Advisor Eugene Long, Associate Warden Adelaido Martinez, Superintendent of Correctional Security Manuel Koroneos, Chief Classification Officer Steve Dillon, State Police Intelligence Officers Fred Encinias and Robert Ortiz, and representatives from the Attorney General's office.

The discussion that day read like a preview of the horrors to come. Koroneos reported intelligence about a white supremacy group within the prison planning a disturbance - possibly a hostage seizure in Dormitory E-2 - scheduled for spring. Associate Warden Martinez shared that an inmate mentioned in Dr. Orner's January 11 memo had requested a transfer out of E-2 because "E-2 is getting hot." Flood reported that the general mood of the inmates was "quite ugly," and department directors noted that inmates were acting differently in several troubling ways.

The meeting participants discussed the possibility of hostage seizures, potential escape attempts, weapon smuggling, and racial unrest. Every major element of what would actually occur forty-eight hours later was laid out on the table. Yet somehow, the institutional machinery failed to translate these warnings into effective preventive action.

The Administrative Breakdown

Part of the problem lay in the prison's chronic leadership instability. Jerry Griffin, who had become warden in April 1979, was the fifth warden in as many years. The Department of Corrections had seen similar turnover at the secretary level, with five different leaders since 1970. Such rapid turnover at the top created an environment where long-term planning was nearly impossible and institutional memory was constantly being lost.

The week before the riot, Warden Griffin ordered his staff supervisors to review the penitentiary's Riot Control Plan. The plan itself contained detailed procedures for responding to exactly the type of incident that intelligence suggested was coming. It listed trouble signs including increases in transfer requests from particular units, undue tension among the inmate population, and changes in contact between inmates and staff - all symptoms that had been documented in the preceding weeks.

But when staff tried to obtain copies of the plan to review it, they discovered a telling problem: only two copies could be located. For an institution housing over 1,100 inmates with a staff of more than 160 correctional officers, having only two accessible copies of the riot plan represented a fundamental failure of emergency preparedness.

Even more troubling, many of the suspected ringleaders remained in Dormitory E-2. Computer records would later show that only three inmates had been transferred from E-2 to Cellblock 3, and none of these three had been suspected of planning a takeover. At least two inmates whom prison officials did suspect of instigating the possible riot were still in E-2 on the night it began.

The Final Hours

Friday, February 1, 1980, dawned cold and overcast. Throughout the day, additional warning signs appeared that should have triggered heightened security measures. An inmate dropped out of the college program and later told a staff member he was leaving school because he believed a hostage-taking would occur in the school area. A female employee was reportedly told by an inmate earlier that week, "When I come and tell you not to come to work the next day, don't come to work." The inmate never gave the warning, and the employee didn't report the conversation until after the riot.

One guard noted an unusually large congregation of inmates in the corridor on Friday afternoon. The secretary for the Intelligence Officer called in sick that Friday because she feared a disturbance was imminent, though she had no specific knowledge of what was planned.

During the final week, correctional officers had been briefed to remain alert and "keep on your toes" for any possible incidents. But no specific procedures were provided, and the briefings were general enough to be almost meaningless. The warnings had been given, the intelligence had been gathered, the signs had been observed - but the institutional response remained inadequate to the gathering threat.

As Friday evening turned to Saturday morning, the stage was set for disaster. The inmates had been planning, the intelligence community had been warning, and the administration had been aware that something was coming. Yet when 1:40 a.m. arrived on February 2, 1980, the Penitentiary of New Mexico was as vulnerable as it had ever been.

The powder keg was about to explode.

Chapter 2: The Explosion - Hour by Hour

11:45 PM, February 1: The Final Shift Change

The evening wind carried a bite of winter across the desert as the morning watch took over at the Penitentiary of New Mexico. Twenty-five correctional employees, including Captain Greg Roybal and Lieutenant Jose Anaya, reported for duty to oversee 1,157 male inmates. It was a ratio that would have been challenging under the best circumstances - in a maximum-security prison plagued by tension and overcrowding, it was potentially catastrophic.

Captain Joe D. Baca, commander of the outgoing evening watch, conducted the routine shift briefing at 11:45 PM. Baca made no reference to the intelligence warnings that had been circulating for weeks. The atmosphere was routine, almost mundane - the calm before an unprecedented storm.

Captain Greg Roybal, at fifty-two years old and after twenty-one years of service, was a seasoned correctional supervisor. He assigned his officers to their posts with the efficiency of long practice. Fifteen officers and one civilian would work inside the main building housing all 1,157 inmates, while nine others were posted outside the perimeter. The assignments seemed routine, but they would soon prove to be death sentences for some and traumatic ordeals for others.

Midnight: The Count

The official inmate count began at midnight, a standard procedure designed to ensure that every prisoner was accounted for and in his proper location. Officer by officer, dormitory by dormitory, cellblock by cellblock, the count proceeded methodically through the institution. By 12:30 AM, it was complete. Every inmate was present and accounted for. Captain Roybal, satisfied that the numbers matched the official records, officially relieved the evening watch.

But in Dormitory E-2, something was already stirring.

The Brewing Storm in E-2

In the middle of January, several inmates in Cellblock 5 - many of them considered dangerous enough to require maximum security housing - had smuggled yeast and raisins from the kitchen to their dormitory. These weren't ordinary inmates; they were men who had been transferred to Dormitory E-2 only because Cellblock 5 was being renovated. The transfer had concentrated dangerous maximum-security inmates in a medium-security housing unit - a decision that corrections experts would later identify as a critical error.

Using plastic garbage bags placed in boxes, these inmates had been fermenting an intoxicating "home brew" for weeks. On Friday evening, February 1, just after the early evening count at 8:30 PM, a group of these inmates began drinking their potent concoction.

By 10:30 PM, according to later testimony and investigation, they were drunk, angry, and talking loudly about "taking over the place." The alcohol had dissolved whatever restraints normally kept their rage in check. The men who had been planning this moment for weeks finally agreed on their course of action: two of them would position themselves in the two single beds nearest the dormitory door and attack when the officers opened it for the routine closing of the day room.

1:09 AM: The Final Patrol

Captain Roybal and Lieutenant Anaya left the officers' mess hall and began their routine walk to the south wing of the penitentiary. Their mission was simple and familiar: conduct a final security check of the dormitories and cellhouses, and close down the day rooms where inmates were allowed to stay up and watch television until 1:30 AM on weekends.

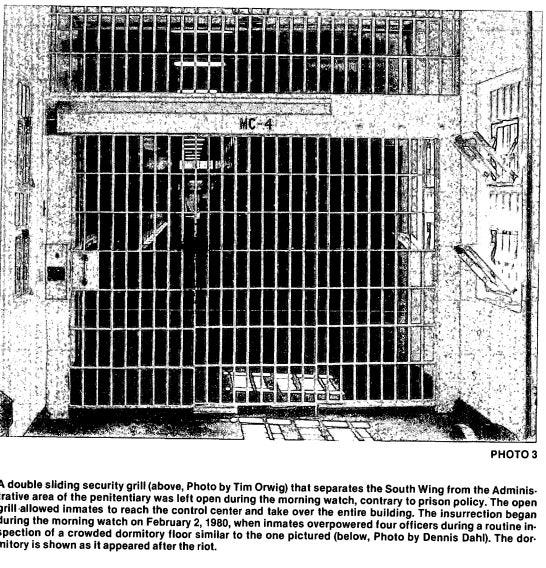

As they walked through the prison, they passed through a corridor grill that separated the South Wing from the Administrative Area. The grill was open - a clear violation of penitentiary policy that required it to be closed and locked during evening and morning watches. Neither officer closed the grill as they passed through. This single security lapse would prove to be one of the most consequential mistakes in American correctional history.

Following customary procedures, Roybal went to help secure Dormitories B and E, working with Officer Michael Schmitt and Officer Ronnie Martinez. Meanwhile, Officers Elton Curry, Juan Bustos, and Victor Gallegos began closing down Cellhouses 1 and 2 and Dormitories A and F. Lieutenant Anaya headed to Dormitory D-1 to assist Officer Michael Hernandez.

The routine was well-established, familiar, almost monotonous. None of the officers had any reason to suspect that this night would be different from hundreds of others.

1:40 AM: The Attack

In Dormitory E-2, the lights had been turned off as part of the day room closing procedure. The only illumination came from a few small blue night lights in the ceiling - but these hadn't been working for over a month. An officer had written a memo requesting repairs, but nothing had been done. The dormitory was plunged into darkness, with only faint light filtering in from the lavatory and the perimeter fence outside.

The darkness was more than an inconvenience - it was a death trap. Dormitory E-2 housed only sixty-two inmates but contained ninety beds, requiring that beds be double-bunked and placed perpendicular to the walls. This arrangement created twenty-eight potential hiding places between sets of bunks. In the darkness, it was impossible for the officer at the door to distinguish between officers and inmates when the staff members were near the day room.

As Captain Roybal, Officer Schmitt, and Officer Martinez prepared to close the day room, they followed the standard procedure. Martinez, who held the keys, unlocked and opened the door. Roybal and Schmitt entered the dormitory, with Roybal taking the right aisle and Schmitt the left. Lieutenant Anaya arrived shortly after and entered behind them.

The two inmates who had volunteered to attack the door were waiting in the beds closest to the entrance, just five feet away. As Roybal progressed two-thirds of the way down the right aisle and Schmitt reached the day room, the trap was sprung.

One inmate leaped from his bed and struck the open door. His partner followed, attempting to knock the door wide open. They were quickly joined by other inmates who had been waiting in the darkness.

The attack was swift and overwhelming. Roybal and Anaya were both middle-aged men of average physical fitness. Schmitt was younger and larger, but all three were simply overwhelmed by numbers. These inmates had been lifting weights regularly and were much younger and stronger than their victims.

Martinez struggled desperately to force the door shut from the outside, but the inmates' momentum was too great. All four officers - Martinez, Roybal, Anaya, and Schmitt - were quickly overpowered. Schmitt managed to throw his car keys and the day room key out a window before being subdued, but it was too late. The inmates stripped, bound, and blindfolded all four officers.

In less than five minutes, the riot had begun.

1:45 AM: The Expansion

An inmate dressed in Captain Roybal's uniform led other inmates down the stairs between dormitories E-2 and E-1. They passed through the unlocked gate at the bottom of the stairs and ran through the open, unused riot control grill into the main corridor. The security systems that should have contained the incident had already failed.

The group ran north along the corridor and up the stairs to Dormitory F-2, where Officers Curry, Bustos, Victor Gallegos, and Herman Gallegos were preparing to secure the unit. The attack was sudden and vicious. Officer Curry offered resistance and was stabbed, beaten, and finally subdued. The inmates took Curry and Victor Gallegos to the E-2 day room to join the other hostages.

In the confusion, Herman Gallegos managed to run into the day room of F-2, where sympathetic inmates protected him from the rioters. But the damage was done. The inmates now had keys to dormitories throughout the South Wing, and within minutes, more than 500 inmates had free access to the main corridor.

The residents of Dormitory E-1, a semi-protective custody unit, barricaded themselves inside their dormitory, sensing the danger that was rapidly spreading through the institution.

1:57 AM: The Race for Control

Officer Lawrence Lucero was manning the Control Center when he heard an inmate's voice crackle over the two-way radio. The message was chilling in its simplicity: the shift captain had been taken hostage. The voice demanded a meeting with the Governor, representatives of the news media, and Deputy Corrections Secretary Felix Rodriguez.

Within moments, Lucero received a telephone call from Officer Michael Hernandez in Dormitory D-1, reporting that inmates were loose throughout the south side of the prison. Hernandez had locked himself in the educational wing, delaying his eventual capture.

Lucero immediately called Officer Valentin Martinez in the North Wing and ordered him to close and lock the far north corridor grill. Then he placed the call that would alert the outside world to the unfolding catastrophe: at approximately 2:00 AM, he telephoned Superintendent Koroneos at his residence on the prison grounds.

Meanwhile, Officers Larry Mendoza and Antonio Vigil were finishing their meal in the officers' mess hall when they heard the disturbance erupting in the South Wing. From the mess hall door, they could see a group of inmates kicking a naked man - later identified as Officer Bustos - in the corridor near Dormitories A and F.

Mendoza observed that the south corridor grill, located midway between the mess hall and the rioting inmates, was open. He quickly calculated that there was insufficient time to secure the grill before the inmates reached it. The two officers ran north up the corridor and pounded on the Control Center window, shouting for Lucero to unlock the north corridor grill electronically. They made it through just as the flood of rioting inmates reached the administrative area.

2:02 AM: The Breaking Point

The scene at the Control Center was surreal and terrifying. From inside the glass-enclosed security nerve center of the prison, Lucero and Officer Louis C de Baca - who had entered the building from his outside patrol to assist - could see a crowd of seventy-five to one hundred inmates gathering in the main corridor.

One of the inmates at the front of the crowd demanded that Lucero open the grills adjacent to the Control Center, which would give the inmates access to the front offices and administrative areas of the institution. When Lucero refused, the inmates began beating Officer Bustos with steel rods and pipes, telling the Control Center officer he could expect the same treatment if he didn't cooperate.

Bustos was beaten unconscious, and Lucero, watching from behind the glass, thought the officer had been killed. The inmates then dragged the unconscious hostage southward down the corridor and turned their attention to the Control Center itself.

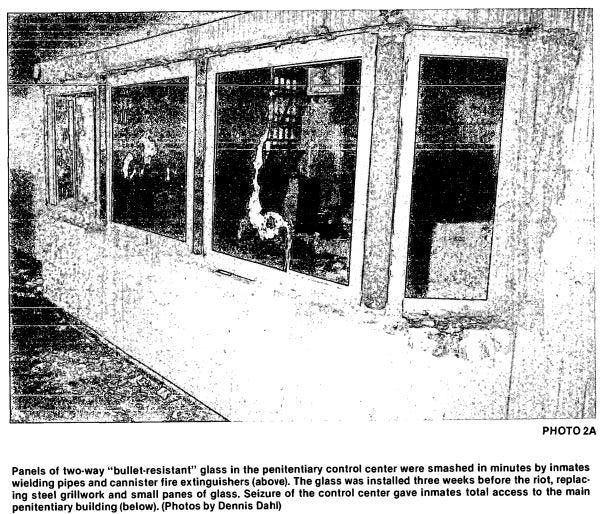

The new "bullet-resistant" glass that had been installed just three weeks earlier became the focus of the inmates' assault. Using pipes, steel rods, and a cannister-type fire extinguisher, they began hammering at the windows. Officers Mendoza and Vigil, watching from behind the north corridor grill fifteen feet away, saw the fire extinguisher bounce off the glass harmlessly on the first two attempts.

On the third throw, the window began to crack.

Believing the glass would hold, Lucero and C de Baca had remained in the Control Center, watching the assault. When fragments began falling from the window with the first serious blow, they realized their position was hopeless. In their panic to escape, they failed to secure any keys from the key board or attempt to use the tear gas stored in the Control Center.

The Control Center contained three baseball-type gas grenades, a tear gas launcher with eleven gas grenades, two helmets, and twenty-four batons. None of these riot control tools were deployed.

At 2:02 AM, twenty-two minutes after the initial attack in Dormitory E-2, the inmates broke through the Control Center glass and gained access to the keys that controlled every part of the institution. In those critical minutes, they had achieved complete control of the Penitentiary of New Mexico.

The Dominos Fall

With the Control Center seized, the inmates now held the master keys to the entire institution. They electronically unlocked the corridor grill leading to the North Wing and rushed toward Cellblock 3, the maximum security segregation unit that housed the prison's most dangerous criminals.

In the North Wing, the remaining officers were desperately seeking refuge. Officer Mendoza returned to Cellblock 3 and called Tower 1, speaking with Koroneos who had arrived at the front entrance. Mendoza's message was stark: the Control Center had been seized, and if help didn't arrive within minutes, the entire institution would be under inmate control.

Koroneos's response - "We're doing all we can" - was small comfort to the officers trapped inside.

Officer Vigil telephoned Tower 3 and informed the officer there that he and Officer Martinez would be hiding in the basement crawl space near the gas chamber. Understanding the danger of radio communications being intercepted, Vigil instructed the tower officer to relay the information by throwing a written note to State Police officers near the fence.

Infirmary Technician Ross Maez locked himself into the upstairs hospital with seven inmate patients. Officers Mendoza, Gutierrez, and Ortega secured themselves in the basement area of Cellblock 3, desperately hoping they could remain hidden until help arrived.

Outside the prison walls, the first calls for help were being made. Officer Hoch in Tower 1 telephoned correctional employee Susan Watts at the Women's Annex, alerting her to the riot. Watts immediately called the State Police and requested that they contact Captain Benavidez to notify the Penitentiary SWAT team.

The cascade of notifications began: Gilbert Naranjo at the Women's Annex, Joanne Brown at the southern facility in Radium Springs, and Security Advisor Gene Long were all alerted. The outside world was beginning to learn that something catastrophic was happening at the Penitentiary of New Mexico.

But inside the walls, the worst was yet to come.

2:15-2:30 AM: Release of the Predators

Using keys from the Control Center, the rioting inmates reached Cellblock 3 and began the process of releasing the men housed in maximum security segregation. These were inmates considered too dangerous, too violent, or too incorrigible for the general population. Many had been placed in segregation for assaulting other inmates or staff members. Some were suspected killers.

The inmates fumbled through the bunches of keys, apparently ignoring markings on the key board that would have identified the correct keys for various units. When they couldn't immediately open Cellblock 3, they brought Captain Roybal from the E-2 day room and attempted to force him to open the unit by threatening his life.

The officers hiding in the basement of Cellblock 3 refused to respond to demands that they open the unit, even when the inmates threatened to kill Captain Roybal. Their refusal was consistent with prison riot policy, which strictly forbade opening secure areas under duress, but it required extraordinary courage to maintain that stance while listening to their captain being threatened with death.

Eventually, the inmates found the correct keys and began releasing the Cellblock 3 residents. The control panel for the upper tiers proved difficult to operate, so Captain Roybal was forced to demonstrate how to use the mechanism. By 3:00 AM, most of the Cellblock 3 inmates were free.

The mixing of different inmate populations - particularly Cellblock 3 segregation inmates with Cellblock 4 protective custody inmates - created a deadly dynamic that corrections experts had long warned against. In the words of one high-ranking corrections official, mixing these populations would "mean certain death."

2:15-2:30 AM: The Pharmacy Raid

Simultaneously with the Cellblock 3 operation, other inmates broke into the hospital and pharmacy. The facility's bulk purchasing policy had resulted in massive quantities of drugs being stored on site: barbiturates, anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, and sedatives were suddenly available to anyone who wanted them.

Medical experts would later note that most of these drugs would typically make inmates drowsy and inactive rather than violent. However, the inmates also gained access to paint, paint thinner, and glue from the shops in the basement beneath the kitchen. Many inmates regularly inhaled the fumes from these substances as intoxicants, and these chemicals were known to induce violent behavior.

The combination of alcohol from the home brew, pharmaceutical drugs, and industrial solvents created a toxic mixture that would fuel the violence to come.

3:00 AM: The Tools of Destruction

Perhaps the most fateful moment of the entire riot came when inmates used keys from the Control Center to access the plumbing shop in the basement under the kitchen. There they found a heavy-duty acetylene cutting torch - a tool that would become both weapon and key to the most secure areas of the prison.

Using this torch, they cut through the manually operated corridor grill separating the Educational Wing and Dormitory D-1 from the rest of the institution. Officer Michael Hernandez, who had been hiding in the unit, was captured and became another hostage. The opening of Dormitory D-1 released eighty-six additional inmates into the general riot.

But the real prize was discovered when the inmates used their torch to break into Cellblock 5, which was closed for renovation. There, left by construction crews, were two additional cutting torches. The contractors had routinely locked their tools in the cellblock during off-work hours, never imagining that inmates would gain access to them.

With three acetylene torches at their disposal, the rioting inmates now possessed the ability to cut through virtually any barrier in the prison. They would use these tools not only to breach secure areas but also to torture and kill other inmates.

Dawn: The Moment of Truth

As the first pale light of dawn began to appear over the high desert, the situation inside the Penitentiary of New Mexico had become a nightmare beyond imagination. In less than five hours, a routine security procedure had exploded into complete institutional chaos.

Twelve officers were being held hostage. More than 1,100 inmates were loose within the main building. The most dangerous criminals in the state had been released from maximum security and were armed with industrial cutting tools. Drug-crazed inmates roamed the corridors with makeshift weapons.

And the killing was about to begin.

The careful security procedures, the training protocols, the emergency plans - all had failed in spectacular fashion. The Penitentiary of New Mexico had become a war zone, and the war was just beginning.

As the sun rose on February 2, 1980, it illuminated a scene of chaos and brutality that would shock the nation and forever change American corrections. The explosion had occurred, and now came the fire.

Chapter 3: The Killing Fields

The First Death

At 3:00 AM, in the basement of Cellblock 3, the sound of terror pierced the darkness. Hostages and inmates throughout the maximum security unit could hear desperate pleas echoing from a cell on the lower level: "No era yo!" - "It wasn't me!" and "No lo hice!" - "I didn't do it!"

The voice belonged to Archie Martinez, a twenty-five-year-old from Chimayo serving time for escape and violations of suspended sentence. Martinez would have the grim distinction of being the first inmate to die in what would become the most violent prison riot in American history.

The pleas stopped abruptly. Later, inmates dragged Martinez's body out into the yard, his head bearing the trauma that had ended his life. The killing had begun, and it would not stop for thirty-six hours.

The Snitch Hunters

The New Mexico State Penitentiary operated under what corrections officials called "the snitch game" - a system that used the threat of disciplinary action to obtain information from inmates. Prison officials would coerce prisoners to become informants, sometimes subtly, sometimes through direct threats. In the words of one department director, inmates often had to "buy protection by informing."

The system created a climate of fear and suspicion that divided the prison population into predators and prey. Inmates suspected of being informants - whether they actually were or not - lived under constant threat. Those housed in Cellblock 4, the protective custody unit, were automatically assumed by other inmates to be "snitches," regardless of why they had actually been placed there.

The riot gave the predators their opportunity for revenge.

As dawn broke on February 2, groups of violent inmates began systematically hunting down those they believed had betrayed them to the authorities. They moved through the prison shouting "Kill the snitches!" and calling out the names of their intended victims.

What followed was not random violence, but organized, systematic murder.

The Horror of Cellblock 4

Cellblock 4 housed ninety-six inmates on the night of the riot - six more than its official capacity. These men had been placed in protective custody for various reasons: some were suspected informants, others were known child molesters or killers, and some were simply weak or passive inmates who were potential victims of sexual assault. Some were merely in transit to other institutions and had been temporarily housed in the protection unit.

From the early hours of the riot, the residents of Cellblock 4 had listened in terror as the institution exploded around them. Through their barred windows, they could see across a short expanse of yard into Cellblock 3, where men were being released from their cells. Many initially hoped that prison officials would quickly quell the riot, so they weren't immediately alarmed.

But as hours passed and the sounds of violence grew closer, the protected inmates began to prepare for the worst. Some barricaded themselves in their cells with metal bunks. Others tied their cell grills shut with towels and blankets. They flashed SOS signals with their lights, desperately trying to summon help from the state troopers they could see stationed outside the perimeter fence.

"We started calling for guards," one survivor later recalled. "There weren't any guards there... we were flashing SOS's with our lights trying to get those cops to come in and they wouldn't come in. I mean all the state troopers that were parked all up and down the fence, man... why didn't they come in? The back door was right there."

But officials had no way to respond. The emergency set of keys in Tower 1 was incomplete - while there was a key to the back door of Cellblock 4, there was no key to the grill that controlled entry into the cell area itself.

The Execution Squads

Just after dawn, the rampaging inmates finally cut through the Cellblock 4 entrance grill with their acetylene torches and gained access to the protective custody unit. What happened next was methodical, systematic murder.

Witnesses described "execution squads" moving from cell to cell, designating their victims while waiting for cutting crews to torch open the cell doors. The killers showed their targets no mercy and no quick death. Some inmates, desperate to avoid recognition, masked themselves with strips of torn blankets and were able to deny their identities and save their lives. But many others were not so fortunate.

The violence was medieval in its brutality. Inmates threw flammable liquids into locked cells, then ignited them, burning their victims alive. When cells were finally opened, victims were dragged out and subjected to unimaginable torture. They were stabbed repeatedly, bludgeoned with makeshift weapons, burned with the acetylene torches, hanged, and literally hacked apart.

The three-story open space of Cellblock 4 became a killing floor. Victims were thrown from upper tiers to the basement, where many of the bodies were later found. In some cases, inmates were tortured for hours before being killed.

The Victims of Cellblock 4

Twelve men died in Cellblock 4, each death representing not just a statistic but a human being whose life was ended in unimaginable horror:

Michael Briones, twenty-two, from Albuquerque, serving time for criminal sexual penetration. Found in the basement with a foreign object driven through his head.

Donald Gossens, twenty-three, from Farmington, serving time for possession and sale of narcotics. Found in the basement of Cellblock 4, victim of massive head trauma.

Phillip Hernandez, thirty, from Clovis, serving time for breaking and entering. Found in the basement, his head crushed and body bearing multiple stab wounds.

Valentino Jaramillo, thirty-five, from Albuquerque, serving multiple drug sentences. Found hanged in a middle-tier cell.

Ramon Madrid, forty, from Las Cruces, serving time for burglary and drug possession. Found burned in a third-tier cell, killed with the very torches that had opened his cell.

Paulina Paul, thirty-six, a Black inmate from Alamogordo serving time for armed robbery and aggravated battery. His body was brought to the front gate, decapitated, bearing multiple stab wounds.

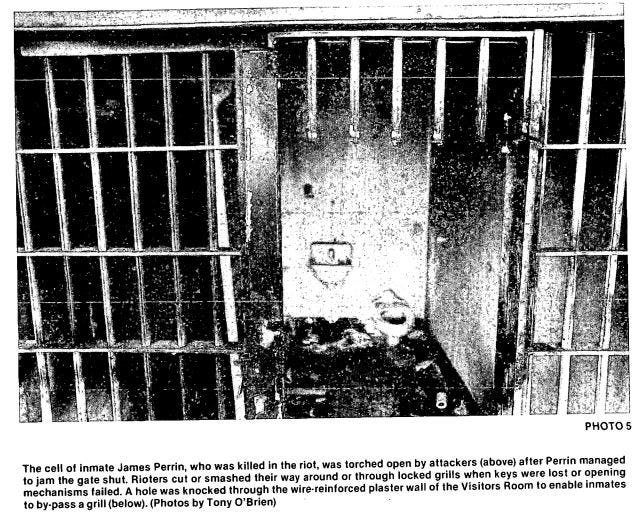

James Perrin, thirty-four, from Chaparral, serving life for first-degree murder. Found at the basement entry, burned, stabbed, and beaten beyond recognition.

Vincent Romero, thirty-four, from Albuquerque, serving time for armed robbery. Found in basement cell 41, victim of massive head trauma and neck wounds.

Larry Smith, thirty-one, from Kirtland, serving life for armed robbery. Found at the front entry of Cellblock 4, his head crushed.

Leo Tenorio, twenty-five, from Albuquerque, serving time for contributing to the delinquency of a minor and escape. Found in front of basement cell 76, stabbed through the heart.

Thomas Tenorio, twenty-eight, also from Albuquerque, serving time for robbery. Found in the basement, stabbed in the neck and chest.

Mario Urioste, twenty-eight, from Santa Fe, serving time for receiving stolen property and shoplifting. Found at the main entry to Cellblock 4, beaten to death and bearing rope marks around his neck.

Death in the General Population

While Cellblock 4 bore the brunt of the systematic killing, violence erupted throughout the institution. In Cellblock 3, where it all began, several more inmates died. Nick Coca was found in the Officers' Mess Hall, dead from carbon monoxide poisoning. Juan Sanchez was shot in the face at close range with a tear gas launcher and left in his cell. Lawrence Cardon was found in cell 32, stabbed multiple times in the neck and chest.

Kelly Johnson, another Cellblock 3 resident, was found burned in the gymnasium, along with Thomas O'Meara from Cellhouse 2 and Filiberto Ortega from Dormitory B-1. The gymnasium had become an inferno during the riot, and the burned remains of the three men were not identified until teams of anthropologists examined the charred bones.

In the dormitories of the South Wing, six residents of Dormitory F-1 were killed: Richard Fierro, Ben Moreno, Gilbert Moreno, Robert Quintela, Robert Rivera, and Russell Werner. Three residents each of Dormitories A and B were murdered: from Dormitory A, Joseph Mirabal (killed in Cellblock 4), James Foley, and Danny Waller; from Dormitory B, Joe Madrid, Filiberto Ortega, and Frank Ortega.

Residents of Dormitories A and B also suffered the greatest number of non-fatal injuries during the riot, including numerous rapes and savage beatings. The first wounded inmate to be treated by medical personnel on Saturday morning was a resident of Dormitory A-1 whose head and arms had been attacked with a meat cleaver.

The Angels Among Demons

Remarkably, amid the savagery and systematic murder, acts of heroism and compassion also emerged. The violence was perpetrated by a relatively small number of inmates - perhaps fifty to seventy-five out of more than 1,100. Most inmates either tried to escape the chaos or actively worked to help others.

An inmate known only as "Doc" worked as a paramedic throughout the riot, moving fearlessly through the violence to dress wounds and provide medical care to both inmates and hostage guards alike. Over the radio, he could be heard giving medical assessments: "I'm over here checking this Lt. Anaya. I think Anaya's got a concussion, and I think he's got a busted rib, and I know that he's got a heart condition and he needs to be moved, he needs to be taken out of here."

Many inmates carried wounded convicts and those who had overdosed on drugs out into the yard, risking their own safety to save others. Some used their roles as stretcher bearers as opportunities to escape, but others returned inside repeatedly to help more victims.

Perhaps most remarkably, several inmates actively protected the hostage guards from other prisoners who wanted to harm them. The officers held in the North Wing were treated relatively well compared to those in the South Wing - they were given food, coffee, and cigarettes, and were shielded from attacks by violent inmates.

The Great Escape

While some inmates were killing and others were trying to help, the largest group was simply trying to escape the nightmare unfolding around them. Starting in the early hours of the riot and continuing throughout the thirty-six-hour ordeal, inmates broke out of the prison through any opening not controlled by the rioters.

The first mass escape came from Dormitory E-1, the semi-protective custody unit directly above the dormitory where the riot had started. When rioting inmates tried to force the E-1 residents to join the uprising, the eighty-four men inside barricaded their entrance with bunks and mattresses. The rioters attempted to force them out by setting fires at the entrance and throwing tear gas into the unit, but the residents fought back, fanning the smoke and gas back into the corridor.

Using a three-foot wrench that had somehow made its way into the unit, the E-1 residents knocked out a barred window and escaped around 7:00 AM, surrendering to officers near Tower 2. Their escape was the first sign to officials outside that not all inmates were participating in the riot.

Throughout Saturday, inmates continued to break out through holes cut in walls, through windows, and through any opening they could find. Many fought other inmates to reach escape routes. Around 8:30 AM, about twenty inmates used a torch to cut through a metal door at the east end of Cellblock 5 and surrendered to police. Most of these were Cellblock 4 residents who had witnessed the killings in the protection unit.

By 5:15 PM on Saturday, over 350 inmates had fled the penitentiary. By Sunday afternoon, barely 100 inmates remained inside the prison. The majority had voted with their feet, choosing freedom over participation in the violence.

The Hostages' Ordeal

While inmates were being systematically murdered and hundreds were escaping, twelve correctional officers remained trapped inside as hostages. Their experiences varied dramatically depending on where they were held and which inmates controlled their fate.

The officers held in the South Wing - Captain Roybal, Lieutenant Anaya, Officers Schmitt, Bustos, and Curry - suffered the worst treatment. They were repeatedly beaten, kicked, stabbed, and in some cases sexually assaulted. Captain Roybal, as the ranking officer, received particular attention from inmates who blamed him personally for their treatment.

Lieutenant Anaya, at fifty-two years old with a heart condition, was repeatedly beaten and suffered what inmates and medical personnel believed were broken ribs and a concussion. His condition became so serious that even the rioting inmates recognized he needed immediate medical attention.

Officer Curry was stabbed and beaten so severely that inmates eventually released him on Saturday morning, apparently fearing he would die in their custody. Officer Bustos was beaten unconscious early in the riot and continued to receive abuse throughout his captivity.

In contrast, the officers held in the North Wing - Mendoza, Gutierrez, and Ortega - were treated relatively well by their captors. The inmates gave them food and coffee, allowed them to smoke, and protected them from other prisoners who wanted to harm them. Though they remained trapped and terrified, they were not subjected to the systematic abuse inflicted on the South Wing hostages.

Three correctional employees managed to remain hidden throughout the entire thirty-six-hour ordeal. Officers Antonio Vigil and Valentin Martinez hid in the basement crawl space near the gas chamber, while Infirmary Technician Ross Maez secured himself in the upstairs hospital with seven inmate patients.

The Radio Voices

Throughout the riot, the hostage officers were forced to communicate with negotiators outside via two-way radio. Their voices, transmitted over police scanners, provided the outside world with real-time accounts of the horror inside.

"At this moment our lives are in your hands," Officer Mendoza radioed to Deputy Warden Montoya. "What else can I say?"

Captain Roybal was repeatedly forced to relay inmate demands and threats. His voice, strained and obviously under duress, became a constant reminder to negotiators of what was at stake.

Officer Schmitt, broadcasting from wherever he was being held, sent a chilling message to officials considering an assault: "If tear gas is used or building is stormed, I've had it."

These radio transmissions, recorded and preserved, provide haunting testimony to the psychological torture the hostages endured along with their physical abuse.

The Escape of Heroes

Some of the most dramatic moments of the riot came when hostages managed to escape or were released by sympathetic inmates. Herman Gallegos was the first to get out, aided by inmates who helped him sneak past the rioters and reach the main entrance at 5:25 AM on Saturday.

The escape of Officer Victor Gallegos on Sunday morning was particularly remarkable. The twenty-two-year-old ex-Marine had been on the penitentiary staff for only three weeks when the riot began. Sympathetic inmates dressed him in convict clothes and hid him under a bunk in a cell for several hours. Because of his youth and the fact that few inmates knew him, Gallegos was able to pass for an inmate when he left the institution with a group that surrendered to authorities.

Officer Ronnie Martinez also escaped with inmate assistance on Sunday morning, slipping out the rear of the prison with help from prisoners who guided him to safety.

These escapes, often facilitated by inmates who risked their own lives to help, demonstrated that even in the midst of unprecedented violence, human decency could still prevail.

The Toll

By the time the violence ended thirty-six hours after it began, thirty-three inmates were dead and more than ninety others had suffered serious injuries from beatings, stabbings, rapes, and drug overdoses. The medical consequences were staggering: survivors suffered from blunt and penetrating trauma, acute drug intoxication, smoke inhalation, and psychological wounds that would last for decades.

Remarkably, despite the threats, abuse, and torture they endured, all twelve hostage officers survived. Seven suffered serious injuries from beatings, stabbings, and sexual assault, but they lived to tell their stories.

The killing fields of the Penitentiary of New Mexico had claimed thirty-three lives in thirty-six hours, making it the deadliest prison riot in American history. But the horror was not random - it was the predictable result of systemic failures, ignored warnings, and a correctional philosophy that had turned inmates against each other with deadly consequences.

As the violence raged inside the walls, outside a complex drama of negotiation and political maneuvering was playing out, as officials struggled to find a way to end the nightmare without triggering even greater bloodshed.

Chapter 4: The Negotiation Marathon

The Command Post

As chaos erupted inside the prison walls, a makeshift command center formed at Tower 1 and the adjacent gatehouse. What began as a routine correctional facility quickly transformed into the nerve center for one of the most complex hostage negotiations in American history.

Deputy Warden Robert Montoya emerged as the primary negotiator, a role for which he was uniquely qualified. Just weeks before the riot, Montoya had attended a law enforcement course in Crisis Intervention in San Francisco. His recent training, combined with his five years as Deputy Warden, made him the natural choice to handle communications with the inmates.

Warden Jerry Griffin, recognizing Montoya's expertise and the need for clear command structure, deferred to his deputy for the negotiations while maintaining overall authority. Griffin established his residence as the communication link with the outside world, conducting regular briefings with Governor Bruce King and coordinating with state officials.

The strategy that emerged was intentionally conservative: Montoya would insulate the rioters from decision-makers like the Warden and Governor, reducing the likelihood of being forced into quick responses to inmate demands. Every decision would be carefully considered, every concession weighed against the potential cost in human lives.

The First Contact

At 2:30 AM, just thirty minutes after the Control Center fell, the first radio transmission crackled from inside the prison. An inmate's voice, later identified by the code name "Chopper One," delivered a chilling ultimatum: Captain Roybal and other officers had been taken hostage, and if officials tried to storm the institution, the inmates would kill the hostages.

The message was clear and terrifying. The inmates weren't trying to escape - they wanted to negotiate. They demanded meetings with Governor Bruce King, members of the news media, and Deputy Corrections Secretary Felix Rodriguez, who was a former warden and respected by many inmates.

Captain Roybal's voice soon came over the radio, confirming the hostage situation and reiterating the inmates' threats. For negotiators, hearing the shift commander's voice was both reassuring - he was alive - and deeply troubling, as it confirmed that the inmates had substantial leverage.

Montoya's initial response established the tone for the entire negotiation. Rather than making immediate concessions or threats, he focused on gathering information and establishing a dialogue. The inmates had the hostages, but they also needed something from the authorities. That mutual dependence would be the foundation for thirty-six hours of tense negotiations.

Building the Response

As word of the riot spread, law enforcement agencies across New Mexico mobilized. State Police Captain Bob Carroll assumed command of all State Police operations at the scene, with thirteen officers arriving by 2:40 AM. Santa Fe County Sheriff Eddie Escudero brought fifteen deputies, who were deployed around the perimeter alongside the State Police.

The Santa Fe City Police Department contributed their SWAT team, led by Detective Joe Tapia, who also had training in hostage negotiations. Tapia joined Montoya as a consultant and sounding board during the early critical hours.

At 2:35 AM, State Police Chief Martin Vigil called Governor Bruce King with the grim news. King's response was immediate: he called National Guard General Franklin Miles, who began mobilizing two Santa Fe units - the 515th Maintenance Battalion and the 3631st Maintenance Company - with a combined strength of 250 guardsmen. Two Albuquerque units were placed on alert, and the 717th Medical Detachment was activated.

By 7:30 AM, fifty National Guardsmen had arrived at the prison, with more arriving throughout Saturday morning. The military precision of their deployment provided a stark contrast to the chaos inside the walls.

The Media Demands

From the very beginning, inmates made access to news media a central demand. This wasn't simply about getting their message out - it was about legitimacy. The inmates believed that media coverage would force officials to take their grievances seriously and provide protection against retaliation after the riot ended.

The first journalist on the scene was Ernie Mills, a veteran Santa Fe radio commentator and political reporter. Mills arrived around 3:15 AM after being alerted by another reporter. He went first to State Police headquarters for a briefing from Chief Vigil, then rode with a State Police officer to Warden Griffin's residence around 5:45 AM.

Mills's presence created an immediate dilemma for officials. The inmates were demanding media access, but allowing reporters inside during an ongoing hostage situation violated every principle of crisis management. Mills solved part of the problem by volunteering to serve as an advisor to officials rather than as a reporter covering the event. "As soon as I went in, I was no longer a reporter," he later explained.

By dawn, numerous reporters had gathered at the highway entrance, along with friends and relatives of inmates. The crowd grew throughout Saturday, creating a secondary crisis as families desperate for information mobbed any official who appeared. Several reporters had police scanners in their cars, allowing them to monitor the negotiations in real time.

The Governor's Involvement

Governor Bruce King arrived at the penitentiary at 9:15 AM Saturday, but his most significant contribution came earlier, during a telephone conversation with inmates at 8:30 AM. The inmates had placed a field telephone near the main entrance and called State Police headquarters, demanding to speak with the Governor.

King was at police headquarters when the call came through, and he agreed to talk with the inmates directly. The conversation was both revealing and disturbing. The inmates explained that the riot was initiated "just to get somebody's attention" and complained of being treated "like a bunch of kids." They demanded a conference with King, Montoya, and Rodriguez in the presence of news media.

King promised that a table for such a conference would be set up in the prison yard within one hour. One inmate assured the Governor that no one was going to be hurt and that they would surrender the guards and the prison by "three or four o'clock" that afternoon. King promised that the institution would not be stormed by police.

The Governor's direct involvement legitimized the inmates' demands while providing crucial intelligence about their intentions. The promise not to storm the prison was significant - it gave negotiators time to work while reassuring inmates that their hostages wouldn't be endangered by a precipitous assault.

The Demands

Throughout Saturday, inmates presented various lists of demands, ranging from immediate tactical needs to long-term grievances about prison conditions. The first demand list, delivered around 9:30 AM, was relatively modest:

Reduce overcrowding

Comply with all court orders

No charges to be filed against inmates

Due process in classification procedures

10 gas masks

2 new walkie-talkies

Officials immediately provided the gas masks, demonstrating their willingness to meet reasonable requests. But as the day progressed, the demands became more comprehensive and ambitious.

The major demand list, delivered around 3:15 PM Saturday, contained eleven points that addressed fundamental issues in the prison system:

Bringing federal officials to ensure no retaliation would occur against inmates Reclassifying segregation inmates in Cellblock 3 Maintaining current housing assignments until the uprising ended Ending overcrowding through expanded capacity Improving visiting conditions, which officials noted had been implemented two weeks earlier Improving prison food through hiring a nutritionist Allowing news media into the prison, contingent on hostage release Improving recreational facilities through negotiations with the ACLU Improving educational facilities and raising inmate wages from 25 cents per hour Appointing a different disciplinary committee Ending overall harassment through additional training for correctional officers

The official responses were measured and largely positive, but they avoided specific commitments that might be difficult to honor. Officials promised to "take a long, hard look" at problems while noting that many improvements were already under consideration or implementation.

The Hostage Releases

The gradual release of hostages became both a bargaining chip and a measure of progress in the negotiations. Each release provided crucial intelligence about conditions inside while demonstrating the inmates' willingness to give up their most valuable assets.

Herman Gallegos was the first to escape, at 5:25 AM Saturday, aided by sympathetic inmates who helped him reach the main entrance.

Elton Curry was released at 7:02 AM Saturday, dragged out on a mattress after being stabbed and beaten. Officials speculated that inmates released Curry because they feared he would die in their custody.

Michael Hernandez was released at 8:20 AM Saturday after inmates reported he was injured and needed medical attention.

Jose Anaya was released at 8:22 PM Saturday on a stretcher. The lieutenant's release came after prolonged negotiations and was directly tied to the inmates' demand for media access.

Juan Bustos was released at 11:23 PM Saturday, bound to a chair, as part of the agreement to allow NBC cameraman Michael Shugrue inside the prison.

Michael Schmitt was released at 12:07 AM Sunday in exchange for Shugrue entering the prison yard.

Victor Gallegos escaped at 7:52 AM Sunday, dressed as an inmate by sympathetic prisoners.

Greg Roybal was released at 8:15 AM Sunday as negotiations resumed after the overnight break.

Ronnie Martinez escaped at 10:55 AM Sunday with inmate assistance.

Edward Ortega was released at 11:57 AM Sunday.

Ramon Gutierrez and Larry Mendoza were released at 1:26 PM Sunday as the final act of the riot.

Each release followed intense negotiations and demonstrated the complex dynamics inside the prison, where violent inmates coexisted with others who actively protected the hostages.

The Media Breakthrough

The turning point in negotiations came when officials agreed to limited media access in exchange for hostage releases. NBC cameraman Michael Shugrue's entry into the prison on Saturday night represented a significant concession by authorities and a major victory for the inmates.

Shugrue spent about forty minutes inside the prison, video-taping inmates in the visitor's room. Some wore masks during the interview; others showed their faces and gave their names. They complained of poor food, harassment by correctional staff, overcrowding, and lack of recreation.

"I was never threatened," Shugrue reported afterward. "I never saw a gun or knife, although there were a lot of clubs. If I had known then what was going on back there, I never would have gone in."

The irony was stark - while Shugrue was safely conducting interviews in one part of the prison, systematic torture and murder were occurring in other areas. The inmates had successfully compartmentalized their operation, presenting a civilized face to the media while concealing the ongoing atrocities.

The Factions

As negotiations progressed, it became clear that the inmates were not operating under unified command. Three ethnic factions - Hispanic (53% of the population), white (37%), and black (9%) - vied for control of different parts of the prison and the negotiation process.

Hispanic inmates comprised the largest group but lacked unified leadership. Some white inmates modeled themselves after the Aryan Brotherhood, while black inmates organized primarily for self-protection. About a dozen black inmates had converged on Cellblock 4 early Saturday and rescued several intended victims from would-be assassins.

The factional divisions created both opportunities and challenges for negotiators. Multiple inmate spokesmen sometimes delivered contradictory messages or argued among themselves over the radio. But the divisions also prevented any single group from gaining complete control of the situation.

One of the most dramatic confrontations occurred Sunday just before noon, when a large group of Hispanic inmates began chasing a group of blacks in the yard, shouting "kill the blacks." Santa Fe County Deputy Sheriff Leopoldo Gurule ordered twenty National Guardsmen and law enforcement officers to "lock and load," leveling their weapons at the charging Hispanics. With just seconds remaining of a five-minute ultimatum, the attackers retreated.

The Collapse

By Sunday morning, it was clear that the riot was winding down. Hundreds of inmates had escaped or surrendered, leaving only 75-125 inside the prison. The inmate negotiators - Lonnie Duran, Vincent Candelaria, and Kedrick Duran - expressed concerns about retaliation and housing arrangements that indicated they were ready to end the standoff.

The final televised news conference occurred just after noon Sunday, with reporters interviewing the inmate negotiators in an office in the gatehouse, then moving to the prison yard for additional interviews. Deputy Secretary Rodriguez assured the inmates on camera that they would be transferred out of state once the hostages were released.

The negotiations were nearly complete when an unauthorized National Guard helicopter flew over the prison, exciting and angering the inmates who pulled the last two hostages back inside. The helicopter incident threatened to derail the final agreement, but when negotiations resumed, the inmates received renewed assurances about their transfer.

At 1:26 PM Sunday, thirty-six hours after the riot began, the inmates released Officers Gutierrez and Mendoza, the final two hostages. Approximately fifty inmates escaped at the same time, leaving only 75-125 inside.

The riot was over.

Lessons from the Marathon

The thirty-six-hour negotiation represented both success and failure. On one hand, all twelve hostages survived, and the incident ended without a catastrophic assault that might have claimed dozens more lives. On the other hand, thirty-three inmates died while officials negotiated, raising questions about whether a more aggressive approach might have saved lives.

Several factors contributed to the negotiation's ultimate success:

Consistent leadership - Montoya's role as primary negotiator provided continuity and built relationships with inmate spokesmen.

Patience - Officials resisted pressure for quick action, allowing time for emotions to cool and reason to prevail.

Flexibility - Negotiators made tactical concessions (gas masks, media access) while avoiding commitments on major policy changes.

Intelligence gathering - Each hostage release and surrendering inmate provided valuable information about conditions inside.

Multiple channels - Various officials (Montoya, Rodriguez, Mills, Senator Aragon) maintained different relationships with different inmate factions.

But the negotiation also revealed serious flaws in crisis management:

Unclear command structure - Authority was divided between Griffin, Rodriguez, and various law enforcement commanders.

Inadequate planning - The riot control plan was virtually unknown to staff and contained only two accessible copies.

Poor communication - Family members and media received inconsistent and often inaccurate information.

Resource limitations - The lack of complete emergency keys and riot control equipment handicapped the response.

The marathon negotiation saved the hostages' lives, but it could not undo the systematic failures that had made the riot possible in the first place. As officials prepared to retake the prison, they faced not only the immediate challenge of securing the facility but the longer-term task of understanding how such a catastrophe had occurred.

The talking was over. Now came the reckoning.

Chapter 5: Retaking Hell

The Moment of Decision

At 1:26 PM on Sunday, February 3, 1980, as the last two hostages emerged from the smoking ruins of the Penitentiary of New Mexico, a sense of relief mixed with grim determination swept through the law enforcement personnel gathered outside the walls. The thirty-six-hour nightmare was ending, but it was ending with a beginning - the dangerous task of retaking a prison from which most inmates had fled, leaving behind only the most hardcore, the most desperate, and the most dangerous.

The decision to enter the prison immediately after the hostage release was not spontaneous. For hours, law enforcement commanders had been developing and refining assault plans, training teams, and positioning equipment. The moment the final hostages crossed the threshold to safety, multiple forces would converge on the institution simultaneously.

State Police Chief Martin Vigil gave the final order to retake the prison. Governor King had given authority to order the assault to Vigil, Captain Carroll, General Miles, and Deputy Secretary Rodriguez. Corrections Secretary-designate Adolph Saenz, who had arrived from Washington D.C. on Sunday morning, took a visible leadership role in the final moments.

As Officers Gutierrez and Mendoza were escorted to safety, Saenz shouted "Move out!" to the assembled SWAT teams. The retaking of the Penitentiary of New Mexico had begun.

The Assault Plan

The strategy for retaking the prison reflected lessons learned from previous hostage situations and riot control operations, but it was complicated by the unique characteristics of the New Mexico facility and the unprecedented nature of the violence that had occurred inside.

The 22-man State Police SWAT team, divided into Northern and Southern units under Lieutenants Raul Arteche and M.J. Payne, would enter through the main entrance and advance to the Control Center. From there, they would split up to secure the North and South Wings systematically.

Simultaneously, the 15-man Santa Fe Police Department SWAT team would enter through the north end of the facility and work southward until meeting the State Police. Five penitentiary employees would accompany the Santa Fe team to provide access to locked areas and assist with inmate transfers.

The National Guard would remain outside the building, positioned inside the double perimeter fence to receive and process inmates as they were brought out. Guardsmen would also maintain security at two arrest-holding areas established in the northeast and northwest corners of the compound.

The tactical objectives were clear: locate and remove the remaining 75-125 inmates estimated to be inside, free the three correctional employees known to be hiding in the building, and preserve crime scenes for later investigation.

Equipment and Preparation

The SWAT teams were equipped with shotguns, helmets, flak vests, and gas masks. Officers received strict instructions about the use of force: firearms were to be used only in response to direct charges by inmates or immediate threats to officer safety. The emphasis was on minimal force and maximum control.

Colonel William Fields of the National Guard issued particularly strict orders: no one was to fire a shot unless he fired first. This restriction would prove crucial in preventing unnecessary casualties during the retaking operation.

Despite their preparation, the assault teams faced significant challenges. Some officers complained that they hadn't received enough information about conditions inside the prison. At least one SWAT team member thought the three hidden correctional employees were actually hostages. Others were unfamiliar with the prison's layout and had to rely on small, inadequate maps.

The teams also discovered that much of the riot control equipment normally stored at the prison was either destroyed in the fire or inaccessible due to damage to the building. They would be entering a facility where normal security systems had been compromised or destroyed.

Going In

At approximately 1:30 PM, the State Police SWAT team entered through the main entrance and immediately encountered two inmates armed with knives in the reception area. The confrontation that many had feared would be violent proved anticlimactic - the police disarmed the inmates without incident and escorted them to the front yard.

The team then made its way through ankle-deep water to the Control Center, but they couldn't follow normal routes. Rioting inmates had beaten holes through steel-reinforced plaster walls to circumvent locked grills after fire and water damage had ruined the electronic opening mechanisms. The SWAT team climbed through a hole in the visiting area wall and through another opening in an office wall to reach their objective.

At the Control Center, officers made a grisly discovery: three bodies lay in and around the facility's nerve center. Gilbert Moreno was found inside the center enclosure, Joe Madrid in a small hallway just south of the center, and Robert Quintela in the main corridor in front of the center. One State Police officer stepped on Moreno's body while climbing through a front window of the Control Center.

The scene was a stark reminder of the violence that had raged for thirty-six hours. As Captain Carroll ordered the State Police Crime Lab team to begin documenting evidence, the magnitude of the investigation that would follow became apparent.

The North Side Entry

The Santa Fe Police SWAT team, accompanied by Deputy Secretary Rodriguez, attempted to enter through the sally port on the north side but immediately encountered problems. Their first attempt to enter through the basement of Cellblock 5 was thwarted by a locked door for which they had no keys.

The team then tried to enter through the west end of Cellblock 4, but again found themselves blocked by a locked grill at the entrance to the living unit. Corrections employee Gene Long, who was accompanying the team, suggested waiting for the grill to be forced open, but the police opted to find another route.

The team finally gained entry through the loading dock behind the kitchen. Sergeant Greg Boynton led six officers to the ground floor of the kitchen while Sergeant Andrew Leyba took six others to check the basement shops, laundry, and physical maintenance areas.

In the kitchen, Boynton's team surprised two inmates and transferred them outside without incident. Long suggested that some officers remain in the kitchen while the rest proceeded, but Boynton rejected the proposal, keeping his team together as they moved into the main corridor.

The Close Call

When the Santa Fe team entered the main corridor, they immediately encountered the State Police SWAT team moving southward from the Control Center. Because the State Police were expecting the city officers to be in the North Wing, the encounter caught them by surprise.

A State Police SWAT team member later reported that the city officers were almost shot before they could identify themselves. The near-miss highlighted the dangers of multi-agency operations in chaotic environments and the critical importance of communication and coordination.

Gene Long had particular difficulty identifying himself to the State Police because the planned system of white armbands for corrections employees had not been implemented. The incident demonstrated how quickly tactical situations could deteriorate even when violence wasn't intended.

Systematic Clearing

Once the two SWAT teams coordinated their positions, they began the methodical process of clearing the facility. Lieutenant Payne's State Police contingent secured the kitchen and found three inmates before moving to the South Wing. As they progressed through the facility, they discovered more bodies: Nick Coca in the Officers' Mess Hall, Russell Werner in the Catholic chapel, Robert Rivera at the entrance to Dormitory A-1, Steven Lucero at the entrance to D-1, and the burned remains of Herman Russell inside A-1.

The officers also noted that the gymnasium was too dangerous to enter due to ongoing fires, but they could see charred remains from the corridor. These would later be identified as three bodies - Kelly Johnson, Thomas O'Meara, and Filiberto Ortega - though identifying them would require teams of anthropologists.

Remarkably, in the midst of widespread destruction, the Catholic chapel remained virtually undamaged - a detail that would be noted by many who toured the facility later.

The Rescue

Santa Fe County Sheriff's officers, acting independently of the planned assault, decided to break into the building from the outside to rescue inmates who were signaling from Dormitory C-1 on the second floor of the burning Psychological Unit. They successfully extracted nine inmates from the dormitory and then moved to Cellhouse 6, where they found twenty to twenty-five more inmates.

The Sheriff's officers' initiative created another dangerous moment when SWAT team members encountered them and initially mistook them for inmates, ordering them to raise their hands at gunpoint. After identifying themselves, the Sheriff's officers continued their operations, with Deputy Eddie Armijo crossing to Cellblock 4, where he found six bodies, and then to Cellblock 3, where he discovered another.

Finding the Hidden

One of the primary objectives of the retaking operation was to locate and rescue the three correctional employees who had been hiding in the prison throughout the riot. The State Police SWAT team successfully found Officers Antonio Vigil and Valentin Martinez in the basement gas chamber area of Cellblock 5, and Infirmary Technician Ross Maez in the upstairs hospital with seven inmate patients.

The rescue of these three men provided crucial eyewitness accounts of the riot from inside the facility. Their survival, after thirty-six hours of hiding while violence raged around them, was remarkable testament to both their own courage and the humanity of inmates who chose not to reveal their locations.

The Killing Fields Revealed

As the SWAT teams moved systematically through the facility, the full scope of the violence became apparent. Cellblock 4, the protective custody unit, proved to be the epicenter of the slaughter. The Santa Fe team found two bodies at the entrance - Mario Urioste and Larry Smith. Inside, they discovered a charnel house that shocked even veteran law enforcement officers.

Sergeant Boynton's team worked from the third floor down while Sergeant Leyba's group worked from the basement up. On the basement level alone, they found four bodies: Leo Tenorio, Michael Briones, Phillip Hernandez, and Joseph Mirabal. The burned corpse of Ramon Madrid was discovered in a third-tier cell, while bodies of James Perrin, Donald Gossens, Thomas Tenorio, and Vincent Romero were found throughout the unit.

The systematic nature of the killing was evident in both the locations of the bodies and the condition in which they were found. Many had been tortured before being killed, and some had been mutilated beyond recognition.

The Final Sweep

In Cellblock 5, the Santa Fe team encountered an inmate sharpening a knife. Upon seeing the SWAT officers, the inmate simply dropped his weapon, saying "I guess I won't be needing this," and surrendered peacefully. The anticlimactic nature of most encounters during the retaking operation contrasted sharply with the violence that had preceded it.

The Santa Fe officers completed their sweep and exited through the front door at approximately 3:30 PM. However, they were ordered to return twenty-five minutes later because of reports that inmates were re-entering the prison from the recreation yard. The second sweep found a few inmates in the basement, who were removed to the recreation yard and secured.

Maintaining Order

Throughout the retaking operation, National Guardsmen maintained control of inmates in the yard and processed those brought out of the building. The strict orders against using weapons proved crucial when an inmate in the yard kicked a Guardsman near the perimeter fence.

The injured Guardsman immediately threw his M-16 rifle over his head to other soldiers, preventing both retaliation and the possibility of the weapon being seized. The incident demonstrated the discipline and training of the Guard units and validated the strict rules of engagement.

The Aftermath of Retaking

The evacuation and treatment of approximately ninety wounded inmates and officers during the riot had been accomplished through cooperative efforts of volunteer, professional, and military medical personnel. Remarkably, despite the severity of many injuries and the emergency conditions, none of the injured died after leaving the penitentiary.

After the facility was secured, firefighters entered to extinguish the numerous fires still burning throughout the complex. They would return the following day for an additional five to six hours of firefighting, as some blazes proved difficult to control completely.

The Human Cost

The retaking operation achieved its primary objectives with minimal additional violence. All remaining inmates were removed from the facility, the three hidden correctional employees were rescued, and law enforcement regained control of the institution. The operation demonstrated that well-planned, disciplined tactical operations could succeed even in the most challenging circumstances.

However, the human cost of the preceding thirty-six hours was staggering. Thirty-three inmates lay dead throughout the facility, victims of the most brutal prison riot in American history. More than ninety others had suffered serious injuries. Twelve correctional officers bore physical and psychological wounds that would affect them for the rest of their lives.

The physical damage to the institution was extensive but repairable. The damage to human lives was permanent and irreversible. As law enforcement officers began the grim task of documenting evidence and removing bodies, they faced a crime scene unlike any in American correctional history.

The retaking was over, but the real work was just beginning.

Chapter 6: Counting the Dead

The Grim Inventory

In the hours and days following the retaking of the Penitentiary of New Mexico, investigators faced the overwhelming task of documenting one of the most extensive crime scenes in American history. The facility had been transformed into a maze of interconnected murder scenes, each telling part of the story of thirty-six hours of unprecedented violence.

Dr. Patricia McFeeley, Associate Medical Investigator, and her staff began the systematic process of tagging and identifying bodies throughout the complex. The work was complicated by the condition of many victims - some had been burned beyond recognition, others mutilated, and several had been moved from their original locations by inmates during the riot.

The official death toll stood at thirty-three inmates, but the process of identifying victims and determining causes of death would take months. Each body told a story of violence that shocked even experienced forensic investigators.

The Forensic Challenge

The State Police Crime Lab team, working in coordination with the Office of the Medical Investigator, faced unprecedented challenges in processing the crime scenes. Many bodies had been moved during the riot, contaminating evidence and complicating the investigation. Some victims had been thrown from upper tiers to basement floors, while others had been dragged to different locations within the facility.

The systematic nature of much of the violence became apparent as investigators worked. In Cellblock 4, the protective custody unit, the evidence suggested organized, methodical killing rather than random violence. Execution-style murders had taken place, with victims selected based on their perceived cooperation with authorities.

The medical examination revealed the full extent of the brutality. Victims had been stabbed, beaten, burned, hanged, and in some cases tortured with acetylene cutting torches. Some had been sexually assaulted before being killed. The violence represented a level of cruelty that stunned investigators accustomed to homicide scenes.

The Demographics of Death

Analysis of the victims revealed disturbing patterns that reflected the racial and social dynamics within the prison. Of the thirty-three dead, twenty-four were Hispanic, seven were white, one was African American, and one was Native American. This distribution roughly corresponded to the overall prison population, which was 49% Hispanic, 38% white, 10% Black, and 3% Indigenous.

However, the locations and circumstances of the deaths revealed more specific targeting. Cellblock 4, which housed protective custody inmates, suffered the highest casualty rate with twelve deaths. These victims were specifically targeted because they were perceived as informants or "snitches," regardless of the actual reasons for their protective custody status.

The age range of victims spanned from nineteen to forty years old, with most being in their twenties and thirties. Many were serving relatively short sentences for non-violent crimes, making their brutal deaths even more tragic.

The Survivors' Stories